SF Masterworks #1: The Forever War, by Joe Haldeman

Spoiler Warning: This review gives away the plot of the book. Completely.

'Tonight we're going to show you eight silent ways to kill a man.' The guy who said that was a sergeant who didn't look five years older than me. So if he'd ever killed a man in combat, silently or otherwise, he'd done it as an infant.

— The Forever War, Opening lines of Chapter 1.

I calculated I had enough money - if I missed lunch - for three books. Alongside The Forever War, I selected Philip K. Dick's Clans of the Alphane Moon and Ursula Le Guin's The Left Hand of Darkness. I had never heard of any of these authors, but I had, from picking up books at the library, heard of the Nebula and Hugo awards. The loud proclamations on the covers of both The Forever War and The Left Hand of Darkness were selling points enough for me. For the Dick novel, I just liked Peter Jones' cover illustration.

I got lucky. The Forever War and The Left Hand of Darkness came very quickly to be regarded as masterpieces. Clans, though I have a considerable affection for it, is regarded as a minor contribution to Dick's oeuvre. Lawrence Sutin, in his excellent Divine Invasions, gives it a 7 out of 10: "an uneven novel, but there's nothing else like it."

For me, at the time, it was The Forever War that made the deepest impact, in particular the opening section, with its depiction of the deadly training regimes of the soon-to-be Space Marines. Even at the time, the Vietnam analog was obvious. I was 12 years old when Saigon fell; though the UK had taken no part in the war, we had traced the progress towards collapse in the daily BBC radio bulletins on our bus ride to school. I remembered the ending as romantic. But when I came, much later, to reread the novel, I found I'd forgotten much of what happens between the breakneck first quarter and the final paragraph.

"Being in combat changes your life completely, usually for the worse. It's not specific things that happen in combat, it's a kind of gestalt - living with horror for day after day after day, and finally you've sort of moved away from the human condition. And you never quite get back, no matter how many years go by. I've seen this in old, old men who were in World War I. I look in their eyes and I see myself. They can never be completely kind. They can never be completely humane."

— Joe Haldeman, interviewed in Locus magazine, 1997

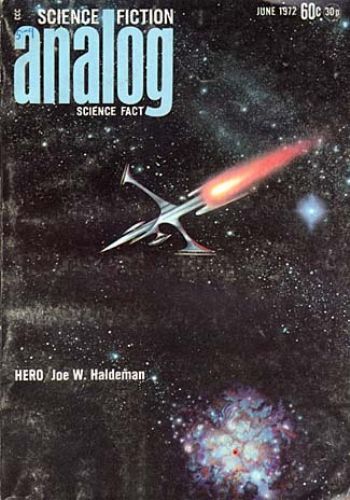

The Forever War was first published as a series of stories in Analog magazine, starting with "Hero" in June 1972. Editor Ben Bova rejected one segment, "You Can Never Go Back", on the grounds of its being "too downbeat"; the original novel replaced this with a more streamlined bridging sequence. By 1976, the book had won both the Hugo and the Nebula.

There are therefore four versions of the novel: the original Analog stories; the 1975 novelisation with the streamlined middle section (the award-winner); a 1991 edition restoring "You Can Never Go Back"; and the 1997 revision cleaning up inconsistencies from that restoration. It's this last version - the author's preferred - that you'll find in current editions, including the SF Masterworks.

This matters. The book you buy today is not the book that won the awards. The version that swept the Hugo and Nebula was essentially censored to make it more palatable - and ironically, by restoring the bleakness, Haldeman made it a more honest reflection of the Vietnam veteran's experience, the very thing he was praised for in the first place. Readers should know they're not reading the same text that won in 1976.

The book's significance rests on several considerations. It was - and remains - a skilfully constructed SF-based liberal critique of the Vietnam War, published shortly after the event, by an author who had actually participated in the war. It was an expression of the alienation felt by returning soldiers, to an American society which had undergone significant transformations in their absence. In both respects, it was early; even outside the SF genre, substantial and authentic works on Vietnam, by veterans or journalists who had been present, were rare. Tim O'Brien's If I Die in a Combat Zone appeared in 1973, Robert Stone's Dog Soldiers in 1974. Michael Herr's Dispatches wasn't published till 1977. Hollywood didn't get round to dealing with the issue until The Deer Hunter in 1978; Platoon, Full Metal Jacket and Jacob's Ladder had to wait till the 80s.

Finally, as a successful liberal critique of "military science fiction", notably exemplified in Heinlein's Starship Troopers, The Forever War revived the sub-genre and turned it on its head. Henceforth, "serious" space opera would require a greater degree of emotional authenticity. Given how much terrible military SF still gets published, this might sound like wishful thinking. But before Haldeman, it was easier to write bad space opera and still be considered a decent SF writer. An early example: Stephen Goldin was working on novelising his 1974 short story, "But As a Soldier, For His Country". Having read The Forever War, Goldin went back, rewrote and re-layered the novel to improve the character and narrative. The result was the unjustly forgotten The Eternity Brigade, published in 1980.

Long distance space travel takes place through "collapsars", instant transportation gateways between star systems. But travel to and from the collapsars necessarily takes place at very high speeds, close to the speed of light. Time spent on campaign accumulates a relativistic debt; the first campaign lasts two years in "real time", but almost thirty years pass on Earth.

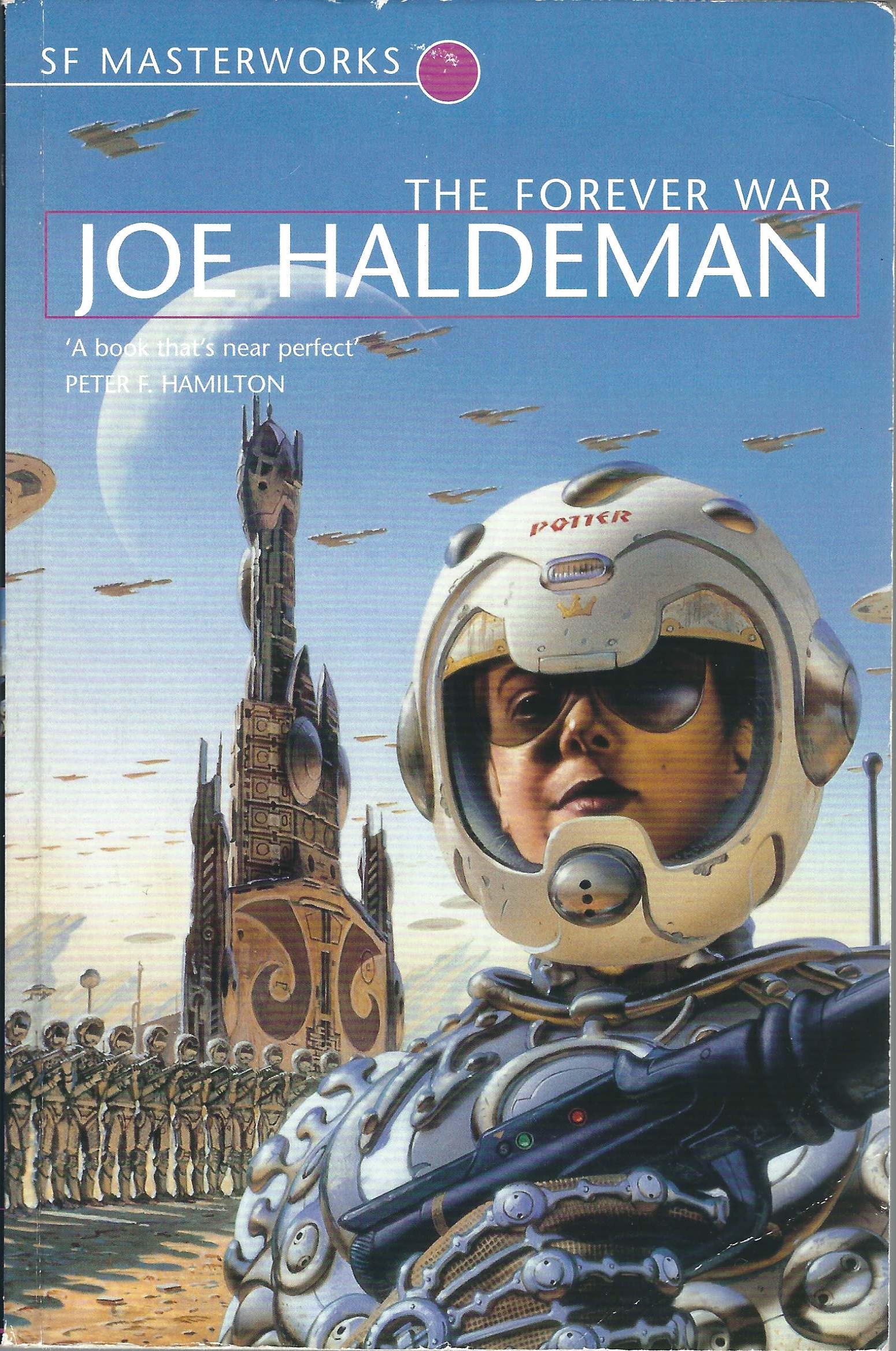

By this time Mandella has fallen in love with one of his comrades, Marygay Potter. The two return to an Earth no longer recognisable. In the 1975 version, the world is strange but functional, and they re-enlist largely out of future shock. In the restored 1997 version, Earth is nightmarish: the economy in ruins, medical care rationed to the point of death sentences for the elderly, gangs roaming freely. Their re-enlistment feels less like a choice and more like desperate flight back to the only safety they know.

Through relativistic accident, Mandella survives the next four years of subjective time while centuries pass on Earth, becoming the war's longest surviving human combatant. All of his original comrades are killed. The army's new recruits are now of a uniform, merged ethnicity and exclusively homosexual. Despite being a senior officer - achieved purely by survival - he's set apart from them by his sexuality, his ethnicity and his archaic version of English. In the final battle, the Taurans are revealed to have been a hive mind all along; the entire war was the result of a misunderstanding, deliberately prolonged by Earth's military-industrial complex.

A thousand years into the future, mankind is now made up exclusively of clones, connected in a hive mind like the Taurans. Mandella is sent to a reserve for the original, uncollective, heterosexual humans. There he's reunited with Marygay, who has been cruising in space, burning objective time, to wait for him. A news item announces the birth of a "fine baby boy".

This was the happy ending I remembered at 13. Haldeman has been at pains to emphasise it isn't. At the end, Mandella and Marygay are living on a reservation - in the 1975 version called "Finger Station", renamed "Middle Finger" in the 1997 edition, Haldeman's final dryly humorous salute to the military-industrial complex and perhaps his original editors. They are evolutionary dead ends, allowed to exist as a courtesy, like a small enclosure for a species that is effectively extinct. The baby is a victory for the individuals, but a total defeat for their kind.

The Starship Troopers Comparison

The comparison to Heinlein's Starship Troopers is unavoidable, though Haldeman has claimed he wrote much of the novel without it in mind. The structural parallels are obvious: elite soldiers, deadly training, powered armour, interstellar war against alien bugs. But the books are ideological opposites.

Heinlein's Mobile Infantry is a meritocracy that works. Military service is the path to citizenship, to meaning, to adulthood. The bugs are genuinely threatening; the war is necessary; the sacrifices are worthwhile. Heinlein served in the US Navy between the wars, was invalided out with tuberculosis, and missed combat entirely. His memories of service were fond. Starship Troopers is the book of a man who regretted not getting to fight.

Haldeman got his fight. He got his Purple Heart. The UNEF in The Forever War is not a meritocracy but a meat grinder that exists - as we eventually learn - largely to perpetuate itself. The Taurans are barely present; we learn almost nothing about them until the war's end, when it transpires the whole thing was a manufactured misunderstanding. The sacrifices were not worthwhile. They were pointless.

If Starship Troopers is a recruitment poster, The Forever War is the VA hospital.

The Time Machine

The relativistic effects mean Mandella ages years while Earth ages centuries. He returns, repeatedly, to a world increasingly unrecognisable. The society he left - heterosexual, ethnically diverse, English-speaking - gives way first to mandatory homosexuality and population control, then to a uniform ethnicity, then to clone consciousness and hive mind.

Wells' Time Traveller visits 802,701 and finds humanity bifurcated into the ethereal Eloi and brutal Morlocks. He's an observer, a tourist with a machine. Mandella has no machine and no choice. And the inversion is telling: he doesn't arrive as a sophisticated Victorian among degenerates. He arrives as the primitive - heterosexual, individual, violent - among the evolved. He's not the Time Traveller. He's the Morlock, lost in a world of Eloi.

By the novel's end, Mandella and Marygay are specimens in a human zoo, preserved on a planet called Middle Finger. The alienation is total.

The Problem of Sex

This creates an odd tension with the novel's earlier sections, which treat female combatants with casual, forward-looking egalitarianism. Marygay is Mandella's equal throughout; the military is integrated without comment. That progressivism makes the later framing more jarring, not less. Haldeman wasn't being malicious - he has subsequently expressed regret - but the mechanism he chose for estrangement has aged in ways he didn't anticipate. SF estrangement devices are powerful precisely because they externalise contemporary anxieties; the risk is that they also preserve those anxieties in amber, visible to later readers in ways the author never intended.

This doesn't invalidate The Forever War. But it does date it, in ways that the physics and the powered armour do not.

Editions and Covers

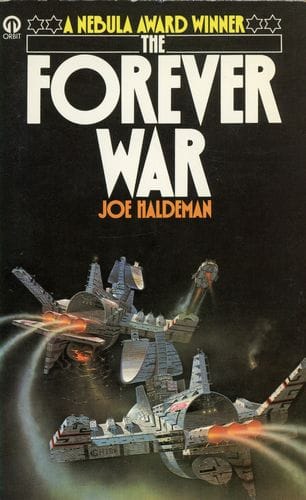

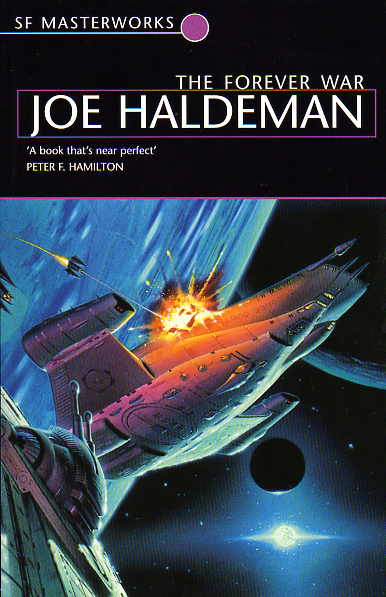

When Millennium initiated their SF Masterworks series in 1999, they selected The Forever War as the first volume - the 1997 author's preferred edition. Gollancz republished it in their 2010 relaunch with an introduction by Adam Roberts and an afterword by Peter Hamilton.

The first three Masterworks covers are by the brilliant Chris Moore. A recent, limited "Best of Masterworks" edition breaks the pattern with a different artist (Autun Purser - and I like the illustrations, although the very idea of this limited series, when the main series is *still there*, annoys me), and there's a difficult-to-find hardcover from an earlier limited series featuring a more expansive version of Moore's original first edition artwork. The yellow-and-white-spined edition was one of the first in the relaunched series, establishing the carcinogenic glow that Gollancz apparently believes sells books. It does not.

Member discussion